Mastermind or Master Mind is a code-breaking game for two players. The modern game with pegs was invented in 1970 by Mordecai Meirowitz, an Israeli postmaster and telecommunications expert. It resembles an earlier pencil and paper game called Bulls and Cows that may date back a century or more.

The game is played using:

The two players decide in advance how many games they will play, which must be an even number. One player becomes the codemaker, the other the codebreaker. The codemaker chooses a pattern of four code pegs. Duplicates are allowed, so the player could even choose four code pegs of the same color. The chosen pattern is placed in the four holes covered by the shield, visible to the codemaker but not to the codebreaker.

The codebreaker tries to guess the pattern, in both order and color, within twelve (or ten, or eight) turns. Each guess is made by placing a row of code pegs on the decoding board. Once placed, the codemaker provides feedback by placing from zero to four key pegs in the small holes of the row with the guess. A colored or black key peg is placed for each code peg from the guess which is correct in both color and position. A white key peg indicates the existence of a correct color code peg placed in the wrong position.

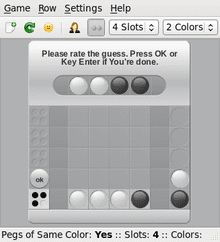

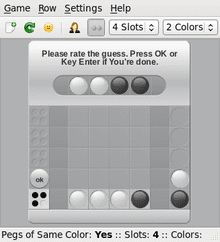

Screenshot of software implementation (ColorCode) illustrating the example.

If there are duplicate colours in the guess, they cannot all be awarded a key peg unless they correspond to the same number of duplicate colours in the hidden code. For example, if the hidden code is white-white-black-black and the player guesses white-white-white-black, the codemaker will award two colored key pegs for the two correct whites, nothing for the third white as there is not a third white in the code, and a colored key peg for the black. No indication is given of the fact that the code also includes a second black.

Once feedback is provided, another guess is made; guesses and feedback continue to alternate until either the codebreaker guesses correctly, or twelve (or ten, or eight) incorrect guesses are made.

The codemaker gets one point for each guess a codebreaker makes. An extra point is earned by the codemaker if the codebreaker doesn't guess the pattern exactly in the last guess. (An alternative is to score based on the number of colored key pegs placed.) The winner is the one who has the most points after the agreed-upon number of games are played.

Other rules may be specified.

Since 1971, the rights to Mastermind have been held by Invicta Plastics of Oadby, near Leicester, UK. (Invicta always named the game Master Mind.) They originally manufactured it themselves, though they have since licensed its manufacture to Hasbro worldwide, with the exception of Pressman Toys and Orda Industries who have the manufacturing rights to the United States and Israel, respectively.

Starting in 1973, the game box featured a photograph of a well-dressed, distinguished-looking man seated in the foreground, with a woman standing behind him. The two amateur models (Bill Woodward and Cecilia Fung) reunited in June 2003 to pose for another publicity photo.

With four pegs and six colors, there are 6 4 = 1296 different patterns (allowing duplicate colors).

In 1977, Donald Knuth demonstrated that the codebreaker can solve the pattern in five moves or fewer, using an algorithm that progressively reduced the number of possible patterns. The algorithm works as follows:

Subsequent mathematicians have been finding various algorithms that reduce the average number of turns needed to solve the pattern: in 1993, Kenji Koyama and Tony W. Lai found a method that required an average of 5625/1296 = 4.340 turns to solve, with a worst-case scenario of six turns. The minimax value in the sense of game theory is 5600/1296 = 4.321.

A new algorithm with an embedded genetic algorithm, where a large set of eligible codes is collected throughout the different generations. The quality of each of these codes is determined based on a comparison with a selection of elements of the eligible set. This algorithm is based on a heuristic that assigns a score to each eligible combination based on its probability of actually being the hidden combination. Since this combination is not known, the score is based on characteristics of the set of eligible solutions or the sample of them found by the evolutionary algorithm.

The algorithm works as follows:

In November 2004, Michiel de Bondt proved that solving a Mastermind board is an NP-complete problem when played with n pegs per row and two colors, by showing how to represent any one-in-three 3SAT problem in it. He also showed the same for Consistent Mastermind (playing the game so that every guess is a candidate for the secret code that is consistent with the hints in the previous guesses).

The Mastermind satisfiability problem is a decision problem that asks, "Given a set of guesses and the number of colored and white pegs scored for each guess, is there at least one secret pattern that generates those exact scores?" (If not, then the codemaker must have incorrectly scored at least one guess.) In December 2005, Jeff Stuckman and Guo-Qiang Zhang showed in an arXiv article that the Mastermind satisfiability problem is NP-complete.

Varying the number of colors and the number of holes results in a spectrum of Mastermind games of different levels of difficulty. Another common variation is to support different numbers of players taking on the roles of codemaker and codebreaker. The following are some examples of Mastermind games produced by Invicta, Parker Brothers, Pressman, Hasbro, and other game manufacturers:

| Game | Year | Colors | Holes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mastermind | 1972 | 6 | 4 | Original version |

| Royale Mastermind | 1972 | 5 colors x 5 shapes | 3 | |

| Mastermind44 | 1972 | 6 | 5 | For four players |

| 2011 | 7 | 5 | Computer vs Human. (Computer always succeeds within 6 guesses.) | |

| Grand Mastermind | 1974 | 5 colors x 5 shapes | 4 | |

| Super Mastermind (a.k.a. Deluxe Mastermind; a.k.a. Advanced Mastermind) | 1975 | 8 | 5 | |

| Word Mastermind | 1975 | 26 letters | 4 | Only valid words may be used as the pattern and guessed each turn. |

| Number Mastermind | 1976 | 6 digits | 4 | Uses numbers instead of colors. The codemaker may optionally give, as an extra clue, the sum of the digits. |

| Electronic Mastermind (Invicta) | 1977 | 10 digits | 3, 4, or 5 | Uses numbers instead of colors. Handheld electronic version. Solo or multiple players vs. the computer. Invicta branded. |

| Walt Disney Mastermind | 1978 | 5 | 3 | Uses Disney characters instead of colors |

| Mini Mastermind (a.k.a. Travel Mastermind) | 1988 | 6 | 4 | Travel-sized version; room for only six guesses |

| Mastermind Challenge | 1993 | 8 | 5 | Both players simultaneously play code maker and code breaker. |

| Parker Mastermind | 1993 | 8 | 4 | |

| Mastermind for Kids | 1996 | 6 | 3 | Animal theme |

| Mastermind Secret Search | 1997 | 26 letters | 3-6 | Valid words only; clues are provided letter-by-letter using up/down arrows for earlier/later in the alphabet. |

| Electronic Hand-Held Mastermind (Hasbro) | 1997 | 6 | 4 | Handheld electronic version. Hasbro. |

| New Mastermind | 2004 | 8 | 4 | For up to five players |

| Mini Mastermind | 2004 | 6 | 4 | Travel-sized self-contained version; room for only eight guesses |

| Mastermind | 2013 | 6 | 4 | digital version |

The difficulty level of any of the above can be increased by treating “empty” as an additional color or decreased by requiring only that the code's colors be guessed, independent of position.

Computer and Internet versions of the game have also been made, sometimes with variations in the number and type of pieces involved and often under different names to avoid trademark infringement. Mastermind can also be played with paper and pencil. There is a numeral variety of the Mastermind in which a 4-digit number is guessed.

There are at least four open-source software implementations of the game concept: