On September 30, 1946, the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany, was a hub of activity. The International Military Tribunal (IMT)—the first major effort to hold a state’s leaders criminally responsible for launching wars of aggression and for perpetrating war crimes and crimes against humanity—was about to render its judgment.

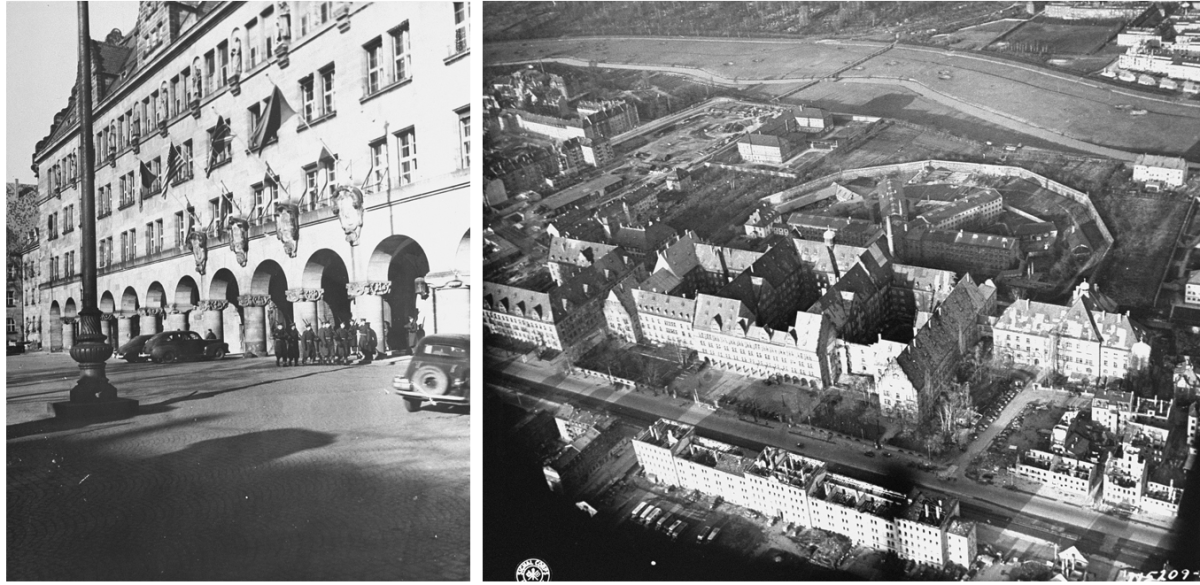

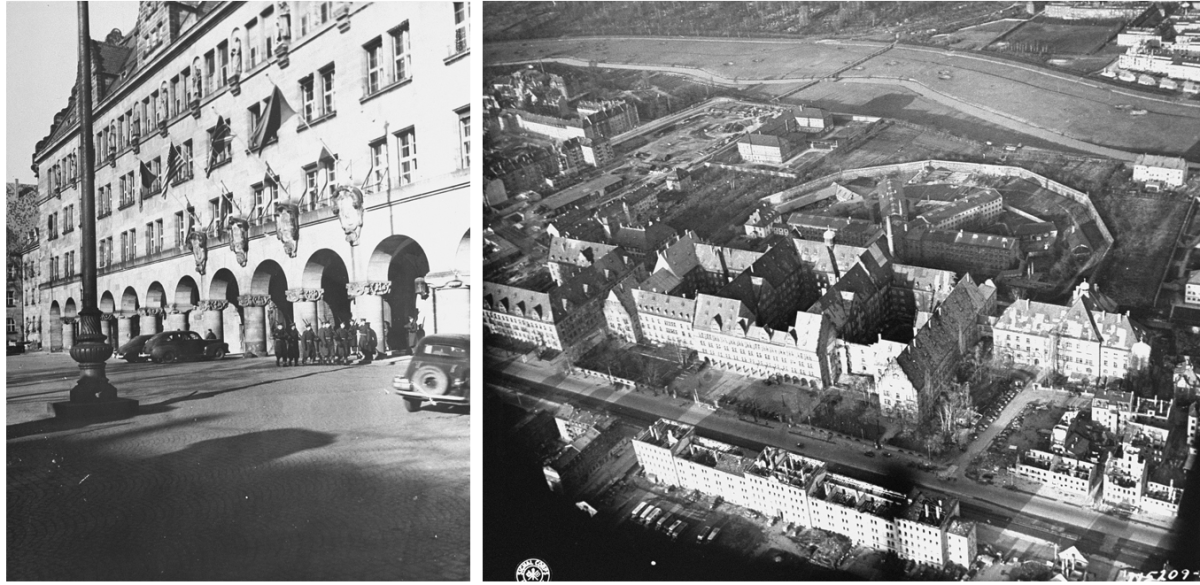

The Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, with the flags of the four countries of the prosecution flying over the entrance. From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library (left). Aerial view of the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg. The four wings of the Nuremberg prison fan out at the back. The defendants were housed in the wing on the far right. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park (right).

Navigating the tight security and throngs of people, the prosecutors and defense counsel settled into their places. Shortly after 9:30 a.m., the crowd watched in silence as the defendants filed into the dock. Everyone stood as the four main judges and their alternates strode in. British judge (and Tribunal president) Geoffrey Lawrence carried the judgement in a thick folder, which drew everyone’s attention.

This was the day everyone had waited for since the end of the Second World War, when the victors had agreed to “stay the hand of vengeance” in favor of a trial.

The IMT had opened on November 20, 1945, with the reading of the Indictment and a few words from Lawrence proclaiming that the trial was “unique in the history of the jurisprudence of the world” and “of supreme importance to millions of people all over the globe.”

For the next ten months, representatives from the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union—the four major Allied powers—had worked together, at times with great difficulty, to bring 22 former Nazi leaders and their organizations to justice.

As the fate of the defendants hung in the balance, the postwar order did as well.

Ideas and arguments about justice, war crimes, and human rights that were articulated in the Palace of Justice over the course of the trials kindled discussions about how to protect humankind from its worst impulses—how to create a new international community based on “respect for the human person” and belief in a “common morality.”

The IMT had prompted discussions about the progressive development of international law. But questions about state sovereignty had dogged it from the start. Everyone wondered how far the judgment would go when it came to Nazi atrocities committed inside Germany’s borders.

The crowd’s attention was now trained on the eight judges as they took turns reading from the judgment. Lawrence described the origins of the Nuremberg Charter and the four main charges set out in the Indictment: conspiracy, war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity.

The other British and French judges (Norman Birkett, Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, Robert Falco) then elaborated on the crimes against peace charge (Count Two)—describing the Nazi conquest of large swaths of Europe.

The American judge, Francis Biddle, introduced the conspiracy charge (Count One)—and a stir went through the courtroom as he explained where the judges and the prosecutors had parted ways. The Tribunal had rejected the prosecution’s argument that the conspiracy had begun with the creation of the Nazi Party in 1920. It had instead dated the conspiracy’s start to the Hossbach Conference on November 5, 1937—when Hitler had revealed to his generals his plans to invade neighboring countries.

Even more significantly, the Tribunal had limited the conspiracy charge to the planning and waging of aggressive war (crimes against peace). The judgment would only concern itself with the conspiracy insofar as it had led to the violent assault on the sovereignty of other states.

The judges turned next to the judgment’s sections on war crimes and crimes against humanity (Counts Three and Four).

The Soviet judge, Iona Nikitchenko, described how Soviet citizens had been forced to support the German war economy by working as slave laborers. He also shared the Tribunal’s finding that the defendants had acted with “consistent and systematic inhumanity” toward Europe’s Jews (referring obliquely to what we have since come to know as the Holocaust).

Nikitchenko then revealed that the persecution and murder of Germany’s Jews before 1939 would not be included in the judgment.

The Nuremberg Charter had limited the “crimes against humanity” charge to crimes committed in connection with another crime under the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. The prosecution had tried to connect pre-war atrocities inside Germany to the Nazi conspiracy. But the Tribunal’s restricting of the conspiracy charge to crimes against peace cut off this possibility.

At 4 p.m. the judges turned to the first part of the verdict: the findings for the organizations.

The SA (Storm Troopers), the Reich Cabinet, and the General Staff and High Command were all not found guilty. The Leadership Corps of the Nazi Party, the SS, and the Gestapo and SD (Security Service) were all found to be criminal—but were deemed culpable only for crimes committed after the start of the war. Here too the Tribunal had chosen to limit the judgment to crimes connected to the planning and waging of wars against other states.

The Palace of Justice was again packed on the morning of October 1. The defendants were back in the dock, awaiting word of their fates. Rudolf Hess sat rifling through papers. Hermann Goering looked around through dark glasses. Wilhelm Keitel, the former head of the Wehrmacht’s High Command, sat stiffly in his military uniform.

This time, the four main judges took turns reading out the verdicts. Goering’s guilt was “unique in its enormity,” Lawrence declared. He was guilty on all four counts. Hess was next, and the verdict was mixed; he was found guilty on Counts One and Two.

German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop’s participation in Nazi crimes was deemed to have been “whole-hearted” and he was declared guilty on all four counts. The verdict against Keitel was the same. Next came Ernst von Kaltenbrunner, the only SS man in the dock, whom the Tribunal found guilty on Counts Three and Four. And so things went down the line. Three of the defendants (Hjalmar Schacht, Franz von Papen, and Hans Fritzsche) were found not guilty—and the Tribunal ordered their release.

At 2:50 p.m. the court held its final session. Now the dock was empty. The defendants would enter the courtroom one by one to hear their sentences. A sliding door behind the dock opened and Goering walked through. Lawrence read his sentence: “Death by hanging.” Hess was led in a few seconds later and heard his sentence of life imprisonment. Ribbentrop was next. “Death by hanging.”

The procession continued. Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, and Julius Streicher were all met with those same three words. Walther Funk and Erich Raeder were sentenced to life imprisonment; Karl Doenitz received a ten-year prison term; and Baldur von Schirach was sentenced to 20 years. Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, and Arthur Seyss-Inquart would hang. Albert Speer received 20 years, and Konstantin von Neurath 15. Martin Bormann received a death sentence in absentia.

The international press had been expecting unanimity from the Tribunal. This was not to be.

Before the crowd dispersed, Nikitchenko recorded his dissent from the three not-guilty verdicts, from Hess’s sentence (arguing that it “should have been death”), and from the Tribunal’s findings about the Reich Cabinet and the General Staff and High Command. Lawrence announced that the dissenting opinion would be attached to the judgment. With this, the International Military Tribunal came to an end.

In the wake of the judgment, important questions lingered. Nuremberg had been an extraordinary event. The judgment would surely have implications for the future of international law. But what were they? How would they be realized?

The United Nations seemed ready to take up the challenge of answering these questions. When its General Assembly met in New York a few weeks later, Secretary-General Trygve Lie urged that the legal principles underlying the Nuremberg Trials—including the principle that heads of state could be held criminally responsible and punished for committing crimes against peace and crimes against humanity—be codified as permanent international law “as quickly as possible.”

Of course, none of this was as simple as it sounded. Some observers, including the New York Times editorial board, warned that the concept of “crimes against peace” was much too vague.

Other observers argued that the Nuremberg judgment had not gone far enough—and declared it particularly shameful that “crimes against humanity” had been defined so restrictively, as a by-product of aggressive war. They called for a broader definition that would include inhumane acts committed by a state against its own population.

On December 11, 1946, just ten weeks after the Nuremberg verdicts, the United Nations General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution affirming “the principles of international law recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and the judgment of the Tribunal.” It then directed the newly established United Nations Committee on the Progressive Development of International Law and its Codification (the Codification Committee) “to treat as a matter of primary importance” the formulation of these principles into a new international law code.

The Cold War derailed the Codification Committee’s efforts, as did the question of enforcement. A number of states, including the United States and the Soviet Union, refused to cede any real sovereignty to international institutions—and especially to any kind of international criminal court. Deliberations over a new international law code collapsed completely in 1952 over disagreements about how to define the term “aggression.”

The end of the Cold War did eventually see the adoption by the United Nations International Law Commission of a Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind (which included crimes against peace and crimes against humanity) in 1996—as well as the founding of the International Criminal Court in 1998.

And the Nuremberg principles have served as an important foundation for international criminal tribunals for Rwanda, Yugoslavia, and other post-conflict states.

But concerns about violating state sovereignty, which were reflected prominently in the Nuremberg judgment, continue to this day. This, together with the recent resurgence of isolationism in America and in other states, have made the kind of international cooperation envisioned after Nuremberg to prevent crimes against peace and crimes against humanity look less and less likely.

Thankfully, stalled efforts by international institutions to end state violence and bring peace to humankind are not the only legacy of the Nuremberg judgment. Over the decades—even as high-level deliberations about international law have foundered—the Nuremberg principles have had an impact at a grassroots level.

They have inspired dissidents, protesters, and civil rights organizations the world over to call out atrocities and to put forward claims for human rights. They have provided a shared vocabulary with which to fight injustice and mobilize for change.

Seventy-five years after the Nuremberg judgment, the Nuremberg principles have retained an undeniable moral power and continue to offer a vision of a world based on “respect for the human person.”